Hyperparameter Tuning LightGBM (incl. early stopping)

This is a quick tutorial on how to tune the hyperparameters of a LightGBM model with a randomized search. It will also include early stopping to prevent overfitting and speed up training time. I believe the addition of early stopping helps set this apart from other tutorials on the topic.

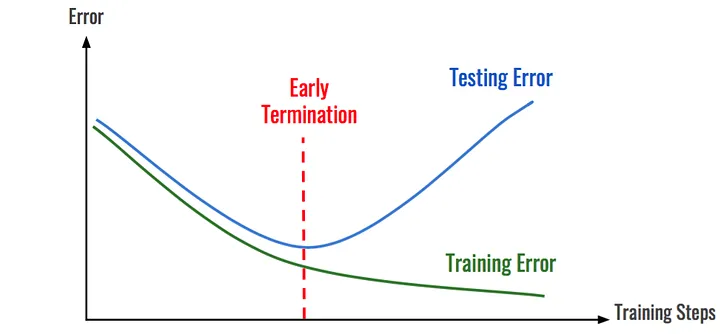

Why early stopping?

Early stopping is great. It helps prevent overfitting and it reduces the computational cost of training. It’s rare to get both of those at once - usually gains to model performance come at the cost of training time (e.g. lower learning rates + more epochs), and vice versa. One of my major takeaways from the acclaimed Deep Learning book is to always use early stopping if possible.

Like neural networks, gradient boosted trees are notorious for overfitting. Early stopping helps prevent this by stopping the training process when the model’s performance on a validation set stops improving. This is done by setting a threshold for the number of iterations the model can go without improving on the validation set. If the model fails to improve on the validation set for a number of iterations, the training process is stopped.

Computational cost is usually the limiting factor of hyperparameter tuning, so we want to decrease it as much as possible. In the mock example above, the training time was cut in half due to early stopping. This is a dramatic decrease, but the reduction in training time quickly becomes apparent when training hundreds or thousands of models while hyperparameter tuning.

Why a randomized search and not grid search?

Between grid search and random search, grid search generally makes more intuitive sense. However, research from James Bergstra and Yoshua Bengio have shown that random search tends to converge to good hyperparameters faster than grid search.

Here’s a graphic from their paper that gives an intuitive example of how random search can potentially cover more ground when there are hyperparameters that aren’t as important:

Source: James Bergstra & Yoshua Bengio

Additionally, grid search performs an exhaustive search over all possible combinations of hyperparameters, which can be prohibitively expensive to perform. Random search, on the other hand, only samples a fixed number of hyperparameter combinations, which can be set by the user. This allows the user to determine how much computational cost they would like to incur.

A quick note on hyperparameter tuning

Hyperparameter tuning helps improve the performance of a model, but it’s important to remember that it’s not the only thing that matters. Obviously it depends on the problem, but data cleaning and feature engineering are often more important to model performance than hyperparameter tuning. Collecting additional data (if possible) may also be more beneficial than hyperparameter tuning and can be checked with a learning curve.

The example

This example uses synthetic data to create a regresion problem. We’ll train a baseline model with the default parameters before performing hyperparameter tuning to see how we can improve on it.

import scipy

import numpy as np

import lightgbm as lgb

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.model_selection import RandomizedSearchCV

from sklearn.datasets import make_regression

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

# Create the dataset

X, y = make_regression(n_samples=300000, n_features=30, n_informative=10, noise=100, random_state=46)

# Split the data into train and test

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y)

# Further splitting the training set into train and validation set for hyperparam tuning

X_train, X_val, y_train, y_val = train_test_split(X_train, y_train)

# Training a baseline model with the default parameters to see if we can improve on the results

baseline_model = lgb.LGBMRegressor(n_jobs=-1, random_state=46)

baseline_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Baseline model -")

print("R^2: ", baseline_model.score(X_test, y_test))

print("MSE: ", mean_squared_error(y_test, baseline_model.predict(X_test)))

Baseline model -

R^2: 0.7203122627948271

MSE: 10316.532016474375

Hyperparameter tuning

We’ll borrow the range of hyperparameters to tune from this guide written by Leonie Monigatti. She compiled these from a few different sources referenced in her post, and I’d recommend reading her post, the LightGBM documentation, and the LightGBM parameter tuning guide if you wanted to know more about what the parameters are and how changing them affects the model.

Credit: Leonie Monigatti

I mentioned above that we can set the number of iterations for the random search. I’m setting it to 40 to keep the runtime short, but you can increase it to be more likely to get better results.

# Defining a new model object with a large number of estimators since we will be using early stopping

model = lgb.LGBMRegressor(n_estimators=10000, n_jobs=-1, random_state=46)

# Define the parameter distributions for hyperparameter tuning

# Using this guide: https://towardsdatascience.com/beginners-guide-to-the-must-know-lightgbm-hyperparameters-a0005a812702

# Parameter documentation: https://lightgbm.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Parameters.html

param_distributions = {

"learning_rate": scipy.stats.uniform(loc=0.003, scale=0.19), # Default is 0.1. Ranges from loc to loc+scale.

"num_leaves": scipy.stats.randint(8, 256), # Default is 31

"max_depth": np.append(-1, np.arange(3, 16)), # Default is -1

"min_child_samples": scipy.stats.randint(5, 300), # Default is 20. AKA min_data_in_leaf.

"subsample": scipy.stats.uniform(loc=0.5, scale=0.5), # Default is 1. AKA bagging_fraction.

"colsample_bytree": scipy.stats.uniform(loc=0.5, scale=0.5), # Default is 1.0. AKA feature_fraction.

"reg_alpha": [0, 0.01, 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 50, 100], # Default is 0. AKA lambda_l1.

"reg_lambda": [0, 0.01, 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100] # Default is 0. AKA lambda_l2.

}

# Configure the randomized search

random_search = RandomizedSearchCV(model,

param_distributions=param_distributions,

n_iter=40,

cv=3,

# cv=sklearn.model_selection.ShuffleSplit(n_splits=1, test_size=.25, random_state=46), # Train/test alternative to k-folds

scoring="neg_mean_squared_error",

n_jobs=-1)

# Perform the randomized search with early stopping

random_search.fit(X_train, y_train,

eval_set=[(X_val, y_val)],

callbacks=[lgb.early_stopping(20)])

# Extract the parameters from the best model to re-train the model

# Update the number of estimators to the best iteration from early stopping

best_model = random_search.best_estimator_

optimal_params = best_model.get_params()

optimal_params["n_estimators"] = best_model.best_iteration_

# Re-train the tuned model

model = lgb.LGBMRegressor(**optimal_params) # Inherits n_jobs and random_state from above

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Tuned model -")

print("R^2: ", model.score(X_test, y_test))

print("MSE: ", mean_squared_error(y_test, model.predict(X_test)))

Training until validation scores don't improve for 20 rounds

Early stopping, best iteration is:

[858] valid_0's l2: 10058.2

Tuned model -

R^2: 0.7247652792608698

MSE: 10152.27852648988

We were able to improve our R^2 score by about 0.5% and reduce our MSE by about 1.5% by tuning the hyperparameters. Let’s see what the optimal parameters were.

# Show the optimal parameters that were obtained

optimal_params

{'boosting_type': 'gbdt',

'class_weight': None,

'colsample_bytree': 0.5762334707881374,

'importance_type': 'split',

'learning_rate': 0.022902997344658664,

'max_depth': 5,

'min_child_samples': 204,

'min_child_weight': 0.001,

'min_split_gain': 0.0,

'n_estimators': 858,

'n_jobs': -1,

'num_leaves': 124,

'objective': None,

'random_state': 46,

'reg_alpha': 2,

'reg_lambda': 0.01,

'silent': 'warn',

'subsample': 0.8578244749533173,

'subsample_for_bin': 200000,

'subsample_freq': 0}

There are ways to continue taking this further, but I want to keep this post relatively short. The next steps I would take would be to increase the number of iterations for the random search, and then potentially use a lower learning rate to fine-tune the model even further. Depending on the problem, there are likely different things that can be done with the data to improve the model as well.

If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to reach out to me on by email or on LinkedIn. Thanks for reading!